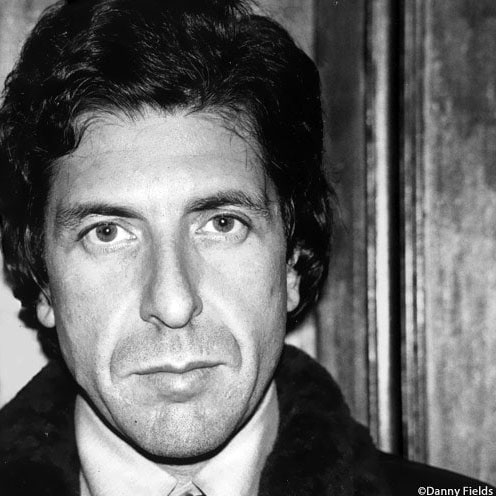

Leonard Cohen interviewed by Danny Fields at the Chelsea Hotel, 1974

Leonard Cohen sat down for a wide-ranging interview with Danny Fields on November 6, 1974, at the Chelsea Hotel, New York City. They discuss how Leonard got into show business, his experiences living in Montreal and Greece, touring Europe, Canadian and American politics, Judaism, his quality of life, thoughts on Fatherhood and family, and so much more.

Poet, novelist, singer, philosopher, romantic hero and legendary lover Leonard Cohen was born in Montreal forty years ago, the scion of a prominent Canadian-Jewish family. By the mid-Sixties, he was a celebrated literary figure in Canada and the United States, and his novel Beautiful Losers was a best-seller. In 1966, Judy Collins recorded a song he wrote called “Suzanne,” and his songs were widely in demand. He began his own recording and performing career in 1967; his fourth studio album, New Skin for the Old Ceremony, has just been released.

This interview took place at seven o’clock on the evening of November 6, 1974, at Cohen’s suite at the Chelsea Hotel, New York City. Present were the interviewer, Leonard Cohen, and his mate Suzanne Elrod, the mother of his two children. She is not the historical Suzanne who takes you down to her place by the river, but she is Suzanne nonetheless.

L: Would you like some vodka?

D: Sure.

L: It’s Harry Smith’s.

S: Leonard says you’re old friends. How far back do you go?

D: 19 … 67. It’s a long time. I think we met at the Newport Festival that year.

L: Danny Fields was my Virgil. He showed me around New York. Help yourself.

D: Aren’t you going to have any?

L: I’m not drinking and smoking these days.

D: Not at all?

L: Not at all.

D: What other disciplines have you imposed on yourself?

L: Well, no virtue accrues to me. It wasn’t a decision I made; it just fell away.

D: Did you smoke a lot?

L: Oh, I was smoking quite a bit.

D: Because I’m taking a course to stop smoking … I just had no faith in myself being able to stop.

L: You know why I really stopped smoking? I had a rival – not a rival for anyone’s hand or anyone’s love. It was just someone who saw me in a comparative way and forced me to look at him that way. And he didn’t smoke. And I said to myself, “If he can do it, then you can do it.” But I think it’s wonderful.

D: What – stopping?

L: No – smoking.

D: Me, too.

L: I love the smell of it – the associations of the stylistic possibilities. I intend to go back to it shortly.

D: Are you here to promote your record?

L: No.

D: How come?

L: Well, I’ll wait to go on tour. I’m going to sing at The Bottom Line on November 28th through the 30th. And then I’m going at the Troubadour in Los Angeles, and then I’m going on a full-fledged tour of the country.

D: What musicians are big in your life right now?

L: Oh, listen … all the guys that are on the album are in my band.

D: Well, they did a splendid job.

L: Didn’t they?

D: Yes.

L: They’re first-rate. And then I have a new big chunk of prose that’s going to my publishers.

D: What will it be called?

L: I think it’s going to be called A Woman Being Born.

D: How long have you been writing it?

L: About three years. Oh, I saw Nico in London.

D: I did, too. When did you see her?

L: About two months ago.

D: That must have been just before she left for Morocco.

L: Yes; she left shortly after I saw her. She was at a lovely hotel.

D: What hotel was that?

L: The Portobello.

D: Oh, because I had been staying there, and she came to visit me, and then she checked in because she thought it was so cute.

L: Yes, and we went to a Japanese restaurant. Nico, and Cindy Cale and our driver. She told me she never goes out, but she made an exception in my case, in deference to our friendship. It was shortly after that that she remarked to someone in the English press, when asked about various figures in the music industry, when he asked her about me, she said, “Oh, he is completely unnecessary.”

D: I know that interview. She let everyone have it. (Laughter) Well, her new album is supposed to be very beautiful.

L: It sure is. I’m a great admirer of her music, and of her person.

“I got into music and into performing – aside from the other obvious things like greed, vanity and ambition – to make a living.”

D: Where are you living now?

L: Montreal and Greece. We spent last summer in Greece.

D: When is the last time you performed in New York? Was it Forest Hills?

L: Yes it was, a long time ago.

D: Have you played in Europe recently?

L: Yes. We just did 38 concerts. Before we got here.

D: They were all big?

L: They were all big. What do you mean by “big”? They were all sold out.

D: Yeah, that’s what I meant by “big.”

L: And we played Barcelona and Madrid. I was able to dedicate a concert to Federico García Lorca, in Barcelona.

D: You’re the biggest star in the world in Europe.

L: I’m a big act there, no question about it.

D: Do you think it’s because you work there more, or because you pay more attention to Europe than America, or what?

L: Maybe it’s because they can’t understand the lyrics.

D: Do you look forward to the same vast acceptance in America?

L: I don’t think it will happen in American. I think the American tradition can accommodate a personnage like that.

D: What are the dimensions of that personnage in Europe that can’t carry over the ocean?

L: I think that that kind of singer is in the mainstream in Europe, and here it’s an eccentric kind of thing. I really think that the American music is black and Western, and whatever the permutations and combinations of those two things are. I don’t know if a chansonnier really fits into that.

D: Was it a surprise to you that you became so enormous in Europe?

L: It never occurred to me that it would happen. I thought the songs would make their way through the world, but I never thought there would be so much interest in me as a performer. My idea was to be able to make records only. But there’s a very different atmosphere now, and I don’t think one’s privacy is environmental any longer.

D: What do you mean by that?

L: Well, I don’t really think it matters where you are, or where you stand, or whether you keep yourself behind closed doors or whether you’re out on the stage. That doesn’t affect your privacy.

D: And how’s your privacy doing?

L: My privacy is in very good shape.

D: It is?

L: Yes.

D: Are you glad to be able to tell that to the world?

L: I wasn’t aware in any sense that the world was hanging on an answer … but I mean, I feel well. You look well, too. You know, I have children now.

D: What sex are they?

L: The boy named Adam is two, and the girl named Lorca is just three months.

D: Are you a good father?

L: I try to set a good example.

D: Are you going to send them to school? What will you do?

L: I’ll play it by ear. Touch wood.

D: Oh, Leonard forgive me, but I have to bring up the revolution. What happened to it?

L: (Laughs) I think everyone perceives that these are times when the work is on the individual for himself, by himself, and the urgency is for each man to make himself strong. I don’t think anybody is going to put together the whole pattern or understand all the movements.

D: Do you think all hopes for collective strength should be postponed?

L: I think that people should clearly perceive what kind of activity strengthens them and what kind of activity disintegrates them. I think those who have a talent or gift, or are nourished by collective enterprise, should throw themselves in with it, and those who are nourished by another kind of activity should embrace that. I think if there is really a revolution, it’s against tyranny, and part of tyranny is the notion that there’s one kind of thing for everybody to do.

D: How did you get into show business?

L: Well, one of the things was to make a living. You know, my teacher at college used to make this clear to me. He was a working novelist, and people always asked him why he published books, and always waited for some spiritualized answer, whereas it just had to do with making a living.

I think certainly that I got into music and into performing – aside from the other obvious things like greed, vanity and ambition – to make a living.

D: And when you found out you could be a star, beyond making a living?

L: Well, that’s a very precarious vocation. One is never convinced that one is, or if one is, that one can sustain it a day longer. I don’t know too many stars. I don’t know what the lifestyle of a star is. I don’t know what the supportive structure is for that kind of existence, to keep shining brightly all the time. My own personal life is of a different nature, and I suppose that when I appear professionally I have the brief appearance of a star, but my normal life is more that of a literary man. I don’t go to parties. I don’t know any of the people I read about in Interview.

I don’t know what’s going on. I don’t live in New York, and there certainly is no “scene” in Montreal, or any scene there is is French-speaking, and I’m just on the periphery of that. So I don’t see myself in that light very often.

D: Then you have created for yourself a very non-typical existence for a public person, particularly for a performer.

L: I think the value of any performer on a stage is where he comes from. It’s not really so much what he does at the moment, assuming that it reaches a certain level of excellence. The interesting thing for me is what a man or a woman brings from his or her own personal kind of ambience to the stage. I’m only valuable at that moment because I don’t live that star’s life.

Perhaps it will change. Perhaps I could document what it is like to move from a private life to a public life day to day to day. But as of now, when I stand on a stage, I feel I bring my private life there with me, and that that’s what’s interesting or amusing. That’s what’s entertaining about me.

When I see other people perform, I think the same way. When I see Joni Mitchell perform, I think this is really the story of a girl who moved from the prairies to Beverly Hills. When I see myself, I think this is the story of a guy who was born in Montreal and lives there still. And there are different kinds of stories, you know? And I think that’s what’s interesting about all of us.

D: But what of the demands on you as a celebrity, especially in Europe?

L: Well, that’s the thing – I don’t feel any demands. Whenever I meet people that other sources would describe as fans, they are extremely sensitive to the moment, they all seem to possess the grace of the occasion, I never get my arm twisted, and people are extremely pleasant to me.

D: Aren’t you lucky!

L: I just feel that nothing has really changed. I always felt I had an audience, sometimes tiny, sometimes larger, sometimes vast, sometimes falling, sometimes rising. I was aware that there was an audience, that a writer or a performer on whatever level it is has a certain stock-market value that changes according to a number of things, but my life has changed very little since the time I first began to write.

I’m not talking about interior revolution or catastrophes, but the style of life seems to be approximately the same. Maybe I’d like to try something else.

“She (Judy Collins) looks more beautiful than I’ve ever seen her. She’s sweet. She was wearing a cashmere sweater. She liked my album; I liked her movie. We all survived.”

D: You once said that in the future you hope you’ll be regarded as one of the great comics of this era. And yet we know that a large part of your audience perceives you as a rather melancholy figure. Which is it? Really?

L: You present your story, and some parts of the story are very funny, and some parts of the story are rather sad, some are monotonous and some are exciting. I think it’s just how much you understand yourself as a story.

D: Well, I’ll quote a few adjectives that kept recurring as I was going through your press clippings earlier today: morbid, depressing, anguished …

L: Oh, yes, now you bring my memory back. Well, it was mostly for those people that I made that I made that statement. Because especially in the English press, where I’m always characterized as neurotic, melancholy, sad – is if there were nothing in the world to indicate why one man might produce a lament instead of a whoop of joy. They’re always, of course, terribly surprised that someone may approach the world in this particular fashion. But I just get tired of that evaluation of my work, and I suppose I was forced into making that statement.

D: Time magazine used that quote as the last line of their review of Sisters of Mercy.

L: That was a terrible play.

D: Is that what you thought of it?

L: Yes. Suzanne, do you have any of those little cakes? Maybe Danny would like one of those.

D: Oh, thank you.

L: It’s the first thing Suzanne did when she came to New York, was to obtain those.

D: These are astonishing. What are they?

S: I’ve eaten them since I was three years old. They’re from the best pastry shop in Manhattan.

D: It is, indeed.

L: Suzanne, you have a convert.

S: I have many.

D: How do your records sell?

L: They go up and down. I think it has a lot to do with their merit, curiously enough. I think they get exactly what they deserve.

D: What do you think was your best album?

L: Sometimes I think my second one was the best, sometimes I think the first one was the best. Now I think this one is probably the best, in terms of a developed work.

D: Have you been in touch with Judy Collins at all?

L: Yes. She was over two days ago.

D: Have you seen her movie?

L: Yes. First-rate.

D: Isn’t it great?

L: I think she’s fantastic. She looks more beautiful than I’ve ever seen her. She’s sweet. She was wearing a cashmere sweater. She liked my album; I liked her movie. We all survived.

D: This room is nice.

L: Yes, isn’t it? I said to Stanley I didn’t want a suite, but he said, “Leonard, I want you to have this room. I won’t charge you for a suite. This is a classic room. It’s perfect.

D: It’s like Viva’s, only backwards.

L: Yes, it was the other way, with the bedroom on that side. What do you hear from her?

D: Brigid saw her in L.A. She’s writing.

L: Well, you must send my love to Brigid, and to Donald Lyons as well. How is Donald?

D: He’s fine.

L: Donald is great.

(Long discussion about health, exercise and cigarettes.)

https://youtu.be/H4P95cJ-XTc

D: What has come of your wanting to be sexually desirable? That was behind much of the energy behind much of what you wrote about.

L: I think it was the exclusive energy.

D: All right – what happened when you did?

L: I don’t remember; it seems so long ago. It seems foolish to have ever wanted something as foolish as that.

D: When did it start to look foolish to you?

L: I think when I realized the consequences of all this lovemaking. It leads to houses and children, and you really realize what the thing is all about, and how it’s available for everyone, in this day and age. Here was one slaving away at one’s desk, writing poems and songs, hoping to attract girls or boys or whatever it was, and outside in the world, the sexual revolution took place unbeknownst to the author. Everyone was coupling behind every bush, and here he was, still writing the perfect sonnet to attract the girl the next door. It became quite apparent that the average chap who worked on Madison Avenue was in much better sexual condition than most of the pop stars, and was exercising his appetite with greater facility. It’s much better to be the bass player than the star. Everybody knows that. If that’s what you’re interested in getting.

D: Why do you think that is?

L: I think that the kind of visibility that one thought was essential is not attractive to the better sexual partners. On the contrary.

D: But do you recall the moment when you realized, at least to some extent, your work and your fame and your persona were making you more sexually interesting than you perhaps had been previously?

L: It would have been that way had I not, as I said, caught sight of the rest of the world happily coupling. I don’t know. You see, it appears to me just from my brief investigation into, uh, offices, like at the CBS building – it seems to me that the sexual atmosphere there is much more acute than backstage. This is the impression I get walking into any place, almost, where boys and girls are together now. Whereas the performance that moment is not really the optimum condition for that kind of prowling. Because especially as you get older, you get fatally interested in the work itself, and you get involved in your own standards, very, very much. It becomes clear that this is not the best kind of environment to find a lover. But you do get the impression that boys and girls are really getting together now – much more so than when I was growing up.

D: Would you have wanted to be coming of age in this freer sexual atmosphere?

L: I never thought I was born at the wrong time; I never thought it was the wrong century. But it is different, there’s no question.

“Americans are naïve enough to believe that everywhere is better than here. That is the greatest naivete in the world.”

D: How do you live now? What style of luxury do you allow yourself?

L: It would be hard to describe our house in Montreal without seeming that I was being pretentious, on the side of modesty. We live in an extremely small house.

D: Is it in a neighborhood that you aspired to when you were young there?

L: It’s one I always liked. It’s in the East End of town, Portuguese working-class street. Our house is about the size of this room, I would say. It is the size of this room. There’s one-and-a-half levels. It’s very crowded, and I’ve just given my studio over to the babies. I’ll have to get a little apartment across the street. It’s really a beautiful place, and we have a garden. But you should come up and see it. It’s like living in the country in the middle of the city. It’s in what they call a slum, not a fashionable slum like Greenwich Village. But now there’s another writer on the street.

S: Of course the slums of Montreal aren’t ugly, like the slums of any other city. They’re beautiful, and safe.

L: Safe – that’s the thing. Like the little child, Adam, runs on the street and goes into neighbors’ houses. The doors are open, and the children come into our house. You know, if you can stand that sort of thing, it’s extremely nice.

D: Is that what you’ve always had in mind?

L: Oh, I’ve always lived like that. My own personal style of living has changed very, very little. I don’t know what I would do otherwise; what would one do?

D: How about your house in Greece?

L: Also in Greece I have a very, very modest house. I heard it described as a marble palace in a French interview, but it’s not even what you could call a villa – it’s very undramatic, just an old house in an old village up on a mountain.

D: Then what does your financial security or wealth or whatever mean to you in terms of how it makes it possible for you to live?

L: I have no idea of what I can afford and what I can’t afford. Nobody seems to be able to tell me. Apparently, until you actually liquidate your estate, you can never be sure of how much money you have or don’t have. My manager always cautions me on the side of frugality. Suzanne drives a Volkswagen, I stay at the Chelsea. I’ve been doing that from the beginning. Before I made any money I had a beautiful white house in Greece, with a very charming companion, I had a suntan all the time, I swam every day, I had credit at all the stores, the place was uncrowded – life was ideal. Now, at best I stay in one-and-a-half rooms at the Chelsea, and air-conditioned hotels in other cities, and things seem to have gone down. It’s not like it used to be.

D: What are your feelings about the French-Canadian separatist movement?

L: Well, there has clearly been a victory for the French-Canadian spirit. Whether it manifests itself exactly in a separate state or in an associate state, or just in psychic differentiation, it’s quite irrelevant. The fact is that the French-Canadian spirit has triumphed in Quebec. There’s nobody that seriously contests that this is a French state of some kind. But also, certain of my political opinions in the past have been anti-leftist, anti-communist, which stopped me from really throwing my weight in against the Vietnamese war. Because I thought that the communists, or the other side, whoever they may be, because there are sides, were using this battle to weaken and destroy American youth and destroy the American army. I still do feel that way. I feel that America has suffered a terrible defeat. I do feel the youth has been brainwashed by the communists and poisoned, both spiritually and physically, as part of the communists’ conspiracy. I think we have been defeated in a war, and I think America’s been disarmed. I think it’s very weak. I think a country without an army is in a very dangerous position. I think there are many people waiting to carve America up, psychically or actually.

D: It would be interesting, though.

L: When it happens?

D: Yes.

L: What do we care?

D: Who cares? Let them carve it … Are you going to raise your children Jewish?

L: Unless I change my name, I will definitely raise them Jewish.

D: Aside from the fact that they’d be perceived that way.

L: Well, it’s very hard to take that as just a side effect.

D: When they come home from school and say “What am I?”, what will you tell them?

S: I’m very happy I’m Jewish.

L: And you’re not even Jewish. But the leftists have completely brainwashed the Jews in New York City, the Jewish youth, into becoming either indifferent to Judaism or actually espousing the Arab/North Vietnamese case. It’s rather sad to see Jewish leftists being led down the garden path to the ovens, as they had been in another generation. Yes, I would definitely have them know they’re Jews. I was in Sinai, incidentally. I believe in the survival of the Jewish people wherever they are, whether they manifest themselves as a state or a culture. I sang for the troops there. I would have sung for the Arabs, too; in fact, I’m trying to sing in Cairo now. I’m very interested in the Jewish survival, and I’m not totally unaware of what is being specifically done to brainwash young American Jewry.

D: It’s only the best of them that are being brainwashed, though. The masses of them are untouched.

L: That’s true – only the best.

D: Well, I had been wondering if you still felt that way about all that.

L: It’s not something that concerns me, except where I see a threat. Like I didn’t think twice about going to Israel when the war broke out.

D: I mean about you believing that drugs are a communist plot.

L: It’s true. You know that. You know that millions of dollars of heroin were being sent to the boys in Vietnam from China.

D: Sure. But I think that was an enemy plot, not a communist plot.

L: What’s the difference? They happened to be communists.

D: Yes, they happened to be communists.

L: Right – it’s irrelevant that they were communists.

D: It was just a wartime tactical maneuver.

L: But there is a war going on, and they used the idealistic version of communism to weaken their enemies through the youth of the enemy countries. You know, if you can get a whole lot of kids in America to believe that what they’re doing in China is communism, and that it’s idealistic and beautiful and a whole new vision for mankind, it’s going to be very hard to fight those guys when they come over here. They are our enemy.

D: But at least no one in China is starving anymore. Maybe they’re the enemy of starvation.

L: That, too. So are we. There are very few people starving in America. But just because starvation has ended in China under the name of communism is not a reason for American youth to embrace it. You know, Americans are naïve enough to believe that everywhere is better than here. That is the greatest naivete in the world. When somebody asks Lennon, “Well, why do you want to stay in America, the home of fascism and racial oppression?” and he replied something to the effect of “For the same reason you want to stay here, because it’s the best place to be in.” And the reason it’s the best place to be in is because of a certain tradition that is completely unknown in these parts of the world where they embrace communism, and these people that embrace communism, they understand that there’s a war on. Why does everyone believe everything they say except the fact that they’re our mortal enemies and they will bury us? And that they will use every possible means to do so. And that they will put an end to this beautiful, corrupt, very many-hued civilization that we love so deeply. Of course they’re trying to defeat us. They defeated our army, they brainwashed our intellectuals, next they’ll get me – then where will we be? (Laughter)

Don’t take my word. Take Solzhenitsyn’s word – his view was we could have done the same thing in Russia, that we did, without all this bullshit of having to follow Marx and kill millions of people, and put the whole intellectual class in Siberia, and generally make life miserable for everyone. The fact is that communism is not necessarily the best way to get people on their feet again. To me, it’s like a failure of imagination to believe that all social change for the better has to take place under this banner. Because we know that with that particular vision there comes a certain kind of harshness, and a certain kind of intolerance, and a certain kind of one-sidedness that is inhospitable to the very spirit that we think makes life worth living. They put you in jail for smoking grass in America, for a little bit of time, but in Cuba they put you in for good – it’s just a matter of those kind of degrees.

D: What is your most prized material possession?

L: I like these boots.

D: They’re nice. What are they? How high do they go? Oh, I like the toes. It’s hard to get those toes.

L: Well, today we saw a beautiful pair of boots in the window of a store called Botticelli. I imagine they’re extremely expensive. They didn’t take any credit cards.

D: Oh, but any good boots are at least a hundred dollars.

L: I’ll never accustom myself to that.

D: Shoes are different from anything else.

L: Well, I agree with you. But I only buy boots with foreign money that I don’t understand. I know these cost a lot, but I don’t know how much because I paid francs for them. They probably are at least a hundred dollars.

D: Where do you stay in Paris? What’s your routine there?

L: On my last tour, I asked my management not to put me into the first-class hotels that we had been put into on previous tours, because I just it was a difficult thing to do to go from these extremely luxurious hotel rooms and play for people wearing blue jeans and shirts, and we’d go back in limousines to these hotels. I thought there was something – not that I have any objection to either ambiance, but it was the mixture of the two that I thought somehow inhospitable. Anyhow, I was really hoping to be able to find a Chelsea hotels or the Portobello hotels of each city, but I unfortunately found that these hotels don’t exist. So we found ourselves being put into these hotels where there are no bathrooms with the rooms.

D: And that’s over the line.

L: Well, it’s hard. You’ve played three hours, and you’ve traveled ten hours that day, and …

D: Americans need bathrooms.

L: Yes. You shouldn’t have to wait in line to take a bath. So I asked to be upgraded again. But in Paris I generally stay on the Rue des Ecoles, in the university hotels.

D: When was the last time you were in California?

L: Oh, about a year ago.

D: How was it?

L: See, I think the world has disappeared. That’s why I consider this – I mean, I always like to be talked to – but I really consider this like making remarks about the changing weather. It’s all gone, you know, in a way I feel about communism and Judaism and the Red Menace and the Yellow Menace in exactly the same way, and I may discuss these with old friends, but certainly not with new friends.

Danny Fields: What is your most prized material possession?

Leonard Cohen: I like these boots.

D: What’s important to you now?

L: I can’t say.

D: What do you discuss with new friends?

L: I tend not to make too many new friends. I like to discuss something specific, like A-minor or D-minor, or whether the monitor is working. You know, one considers one’s self dead, and the catastrophe has taken place. On the exterior level, the catastrophe is a woman and children you that you thought you never wanted, and would be the worst thing that could possibly happen. But once it happens, and you’ve faced the worst thing that could possibly happen, you feel a lot better. On the interior level, it’s the destruction of your value system, and the complete disintegration of the value of all your opinions.

D: What brought that about?

L: I have no idea, except that that’s why one wanted it to happen.

D: Then you’re relieved and pleased with this disintegration?

L: Yeah, you know I feel like I’m a political animal also, so I’ll discuss communist China. You know, once you’re dead, you’re really dead to those things.

D: Are you really dead to those things?

L: Pretty much so. I give them equal value, like with the weather. I could get very interested in the sunset, or whether it’s going to rain or not, I like to have a suntan, I hope that the people of India don’t starve.

D: Are you looking forward to coming alive to anything?

L: I’m very happy being dead. I’ve never quite felt so good.

D: Do you think declaring yourself dead spares you the embarrassment of being alive?

L: I’m very interested in the physical universe, and in manifesting myself on the physical … as a physical being.

D: So you’re glad to be physically alive?

L: I’m glad to be alive; I’m glad to be dead. Sometimes I think I’m just too old to discuss existence and its various problems.

D: People just want to know what you’re doing these days.

L: I am aware that some of this may find its way into print … Well, a lot of the things I thought were important, not even thought, but felt were important, I don’t have any feelings about any longer. I can’t say I’ve discovered anything or learned anything or achieved anything – it’s just that the whole landscape has withered and shriveled away and blown away. Although you can press the buttons and consider them, like China, the Jews … One is reluctant to say publicly that one feels good, but I do – I feel good. I don’t feel so murderously depressed and suicidal. When I say I feel good I don’t mean I never feel bad, but it doesn’t mean I’m not frightened when I get on the stage. I know that I can fail, that I can humiliate myself and experience the sense of disgrace, but it all happens in a landscape which is completely indifferent to those moods. But it doesn’t mean that you don’t feel them. It’s like that famous story that you probably never heard of this guy visiting an old man who lives in the desert in an extremely hot and arid land, and he says, “How can you exist under these climactic conditions?” and the old fellow says, “Listen – you should see what it’s like in the summer.” And the visitor says, “Well, what do you do then?” And the old man answers, “I throw myself into a pot of boiling oil.” And the visitor says, “But isn’t that worse?” And the old man says, “Pain cannot reach you there.” That’s the way I feel – if you throw yourself into it … the only thing that was bothering me in the past was that I couldn’t throw myself into it.

D: Have you found a place where pain cannot reach you now?

L: Yeah, when you really throw yourself into it. I always thought I’m not ready to have a baby, I’m not ready to be a father, I’m not ready to assume the responsibilities of parenthood, I’m not ready to go on stage when they knock on the door at eight o’clock, “Five minutes, Mr. Cohen.” You know you’re never ready for these things that are the things that create character.

Somehow you have to be tripped in such a way that you’re thrown headlong into the events, and trick yourself by signing up for the tour or spending the money before you’ve made it, or whatever it is, and then you find out that these events create character, these events that you’re never ready for. It’s only the events that you’re ready for that create character, apparently.

D: Is this feeling finding expression in your work now?

L: I think whenever we see something interesting, something that we call interesting, either in the performance on the page or on the stage, I try to think, what is it that’s really interesting about it, and it’s the things that people do that they can’t help. It’s that tick, that twitch – it’s those things that are really interesting about people. That’s why we find the mad so fascinating. And somehow, when you get into that, somehow you can move into a realm where you’re doing more of those things than deciding whether you’ll do them or not. And somehow, that’s … I assume my monsterhood when I go on the stage; I know I’m like this, and it’s … one is free. But I think you have to get tripped.

D: Does this change your attitude toward your audience at all? When you see what they want from you, what they expect from you, what they love about you?

L: I’m very reluctant to speak of that moment, because there still are mysteries, and I have no idea what really goes on, and why it is they tolerate me there, for that hour or two.

D: You still get off on that, don’t you?

L: I’m still awed by it. I still stand in a certain reverence to it. Oh, yes. There’s a beautiful theater in Liverpool, and they gave me a little statuette for having sold it out. And a man who worked in the theater, I think he pulled the curtain, said to me, “Oh, you sent some happy people home tonight, Mr. Cohen.” And that’s another aspect of it that’s so nice.

D: Are you doing as much performing as you’d like to?

L: I’d really like to do it a lot now because there’s no question about it, after a certain point you get better as you learn how to do it. You become freer. I don’t know long the public will tolerate that sort of thing, because we know that the public’s tolerance of things is very brief.

D: Not all the time.

L: Not all the time, but with the majority of artists. There are a few people they allow to remain in their consciousness for a number of years.

D: What would you do if you found yourself out of their consciousness?

L: I’d write about that. What would you do?

D: I’d worry about it when it happened.

L: You don’t even know when it’s happening. You’re probably the last to know. Marty, how come they can’t get me a gig in Boston? They loved me there last time. But I think that people are interested in the phenomenon of survival, and one has, in a sense, become an old-timer on that scene, and one has survived.

D: That’s what I asked before. Do you feel guilty about having survived?

L: Not at all. Anyhow, I’ve always been too old to commit suicide or to go down that way. I was already into my middle thirties when I came into this scene.

D: And you were never victimized by it like, let’s say, Janis was?

L: She was just a girl. She was in her twenties when she died.

D: Twenty-seven.

L: So it really happened to her when she was twenty-five, maybe even earlier, when she became able to command huge audiences. That’s quite young. I believe that between twenty-five and thirty-five, an enormous chunk of undigested experience tends to filter out. I mean, anything can happen to any of us to crush the spirit and make us destroy ourselves, but just the scene itself – I always did have the impression that there was a sense of overdramatization and all the people involved: the artists, the journalists, the critics, taking this thing a bit too seriously. Maybe that came from the fact that I already ran through a whole literary episode which had in it a microcosm of the same elements operating. I once said somewhere else that I never really believed that Mick Jagger was the devil, or that he represented any diabolical forces that he could unleash on mankind.

D: You planned your entry into show business very cautiously, didn’t you?

L: Well, I’ll go with the word “cautious,” but not the word “planned.” I’m generally cautious. But it wasn’t a matter of planning; it was a matter of when one was strong enough to undertake the kind of activity that would be necessary for you to … you just had to be able to summon a certain stamina to do a tour of 40 cities. You can’t be a junkie, you’ve got to get to the concerts, the record has to be there or CBS won’t promote it – there are a lot of things that have to take place before you can actually mount the operations which involve a certain amount of physical integrity and spiritual integrity – just to hold it together. I would have loved to have made a tour of America some time ago, but I wasn’t strong enough to do it, either in myself or my chart position.

D: When did you know that you were?

L: Well, I don’t know that I am in terms of the chart position, because the record hasn’t come out yet.

####