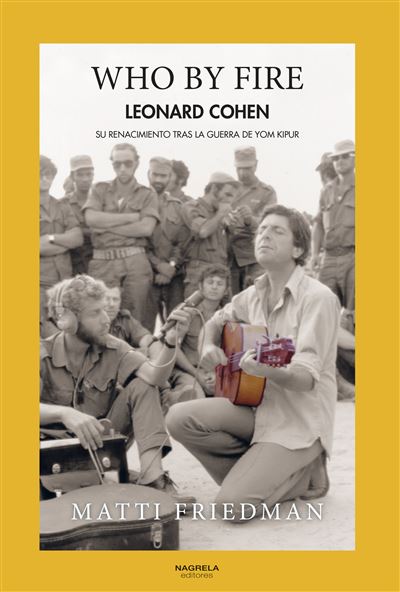

Who By Fire, Leonard Cohen "Su renacimiento

tras la guerra de Yom Kipur" (Leonard Cohen in the Yom Kippur War)

Matti Friedman 2022 ; traducció a l'espanyol xxxx;

Nagrela Editores 2024 192p. ISBN 9788419426284. prestat,

mai comprat, agost 2024.

New Book - Who By Fire, Matti Friedman leonardcohenforum.com

This book offers few new things. I found interesting the references to Cohen's orange notebook and an unpublished short fragment of an interview by Sylvie Simmons with Cohen. The testimonies interviewed are indirect and dubious. The most interesting would have been those of Ilana Rubina and Matti Caspi, but they did not agree to be interviewed. Matti Caspi said that he had nothing to add, that there was no close connection between them and that he does not want to fill in any blank spaces, which seems to me to be an honest attitude. The days of the Yom Kippur war were transcendental for Cohen, but he avoided giving explanations. He was born a Jew, procreated a Jew, died a Jew and went to Sinai alongside his Jewish brothers.

The apparent great contribution is found in a supposed typewritten manuscript by Cohen opportunely discovered by librarian Chris Long in a cardboard box in the McClelland & Stewart archive at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. It was just what Matti Friedman needed to offer something new in his book, “…which was exactly what I was looking for…” he said in an interview.

In chapter 3, Friedman warns us that he has cut and corrected the manuscript. At the end he has left not much. Friedman seems to think he can abbreviate and correct Cohen's work and improve it for Cohen's readers. Great! I have read all of Cohen's published work, including “A Ballet of Lepers”, more than once, and I do not recognize Cohen in this manuscript.

Friedman describes the war scenario that Cohen found from one side of the conflict, this is reasonable. But he gets lost in stories and photos that have little to do with it and that take up most of the book, possibly with a different intention than documenting Cohen's presence. He exposes his radical political point of view closely linked to religion. It is difficult to classify the literary genre of that book, it is not exactly biography. He seems to enjoy recounting war exploits. He shamelessly recounts war crimes as a way of finishing the job (Yukon, chapter 18). (At least that part of the book is not fiction, the criminal has name and surname and we know where he lives with impunity, Friedman interviewed to his admired criminal in 2020).

The ex-military Friedman writes (chapter 20) that the singer who called himself “Field Commander Cohen” and his band “The Army” believe that war is a metaphor or an ironic pose. For the blond commander (here Friedman refers to the criminal) war was a daily terror with real corpses, friends and enemies, fallen in the sand. The poet knows beauty, morality and the criminal who uses violence to create the security bubble where poets can ignore criminal actions; they can even condemn the people who carry them out. Here I see a certain disdain directed at Leonard Cohen, right?

In reality, the criminal does not provide any security, creates hate. On the other side they also fight to defend themselves, they also have their heroes, their martyrs and their criminals. This is how the spiral of violence, pain and terror grows for the enjoyment of the “Masters of War” that Dylan denounced, those who play to increase their geostrategic power.

That war in the desert was between soldiers, they went to kill and die, some survived somehow. Some went voluntarily, some did not. They were soldiers and it was a war. It is not a war when the objective is the annihilation of a people.

Today I have no hope of having your smile,

ForYourSmile, Aug 15 2024.

~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~

More information:

LC and the Yom Kippur war , 1973 - 2005 2014 leonardcohenforum.com

Help - photos of LC from the Yom Kippur war - 2009 2017 leonardcohenforum.com

When Leonard Cohen Performed For Israeli Troops During The Yom Kippur War By David Lange 2016

לאונרד כהן במלחמת יום הכיפורים By Eran Rusk 2019

Ilana Rovina recounts the encounter with Cohen in a Tel Aviv café, similar version to the book (translate.google.com):

"We were sitting in a 'corner' cafe in Tel Aviv, Mati, Ushik, Popik and I - and we got ready for the performance, and Ushik said: 'This man sitting there alone looks like to Leonard Cohen'. I said to him: 'You would have died', but he said: 'Oh dear, it's Leonard Cohen.' he approached him and asked: 'Are you Leonard Cohen?' And the man said: 'Yes'. We invited him to sit with us, we said To him that we are singers and we asked what he was doing in Israel. He said: 'I heard there was a war so I came Volunteer to work in the kibbutzim in the harvest and release some guys to the army. We told him that now there is no harvest And we offered him to come perform with us, so he said he was a pacifist. We told him we were not fighting but perform then he said he didn't have a guitar. "We called Oded Feldman, who was the culture officer of Air Force, and in a second there was a guitar. This is how we moved between the outposts for several months, the soldiers They just didn't believe it. It was at a time when he was an idol in Israel, and he was also very excited. Leonard was then at the height of his popularity, the youth adored him. When the soldiers heard that he was coming to perform To their face, they thought they were being made fun of. When he arrived with us there was an excitement that is simply hard to describe. It was a surreal spectacle”.

McMaster’s Leonard Cohen manuscript By Wendy Schneider 2022

“Cohen never seems to have mentioned it afterwards,” said Friedman. “It was clearly a difficult experience for him, and yet, I didn’t have his own words about what had happened, and that was obviously a gaping hole at the centre of my book project.” When Friedman reached out to Long that day, he was following up on a footnote in a 1990s Cohen biography that referred to a manuscript in the university’s McCLelland and Stewart archive. It felt like a shot in the dark, which turned out to be the case. For Long was unable to find any mention of the manuscript at first, and it was only on further investigation that he found the mystery manuscript in a box in an off-site storage facility in Dundas. “I was astounded by it,” Long, a long-time Leonard Cohen fan, told the HJN, recalling the moment he first laid eyes on the 44-page typewritten document that he immediately scanned and forwarded to Friedman. Friedman was just as excited. “He said very pointedly that the document was fascinating, that it would be very significant to his research and that it was real and raw Leonard Cohen … that was very exciting for us,” Long says. Friedman told the HJN that finding the manuscript felt “like striking gold.” “I hadn’t been sure that this manuscript even existed or that it could be found. And then, suddenly, there it was,” he says. “I opened it and realized what I was seeing, which was exactly what I was looking for. That doesn’t happen a lot in journalism that you get exactly what you were looking for. But here was Cohen in the first person telling us not only what had happened in kind of journalistic language, but also what it felt like in very Cohenesque, often very difficult, sometimes obscene, but always interesting prose.”

The Canadian Jewish News, What was the guy who wrote “Suzanne” doing in the Sinai?’: Matti Friedman talked about Leonard Cohen—and his own writing about Israel—during a visit to Montreal By Hannah Srour-Zackon 2022

The Story Behind Leonard Cohen’s 1973 Concerts for Israeli Troops Fighting the Yom Kippur War By Kim Hughes 2022

"Even if the backstory was begging to be told, it wasn’t easy. For one thing, Cohen didn’t detail it in his notebooks, which Friedman flew to Los Angeles to read. He had to piece together the narrative through interviews with those who saw Cohen play or who had performed in his local pick-up bands; through photographs snapped by soldiers at the shows (many included in Who By Fire); and through a deep dive into the archives of his publisher, McClelland & Stewart, at the McMaster University library in Hamilton, Ont. At McMaster, Friedman uncovered a 45-page manuscript, housed in a box, that Cohen typed on the Greek island of Hydra (where he lived with his partner, Suzanne Elrod, and their son, Adam), shortly after he got back from Israel. “The entire document is too long to print in full,” Friedman writes, “so I’ve taken the liberty – with great trepidation – of abridging the text to distill the narrative of his journey to Sinai.” Even so, the manuscript is cryptic and impressionistic. It is also, as Friedman writes, “often livid and obscene. The way he writes about women, and the way he related to them, was part of the style of those days, but it is out of step with our own times.”

Aya Korem àéä ëåøí - îé áàù (youtube.com)

Unetaneh Tokef (Yair Rosenblum) - Cantor Sydney Michaeli (youtube.com)

~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~

The Geneva Conference / Leonard Cohen Matti Caspi web

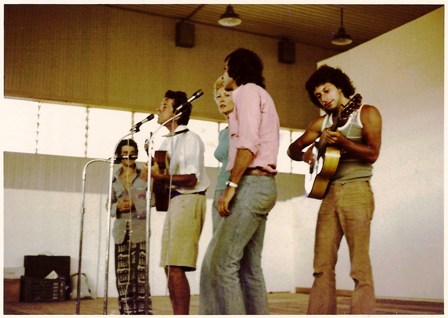

Video and photo from Matti Caspi web:

Ilana Rubina and Matti Caspi - We Have No Words (youtube.com)

Lyrics: Oshik Levy, Ilana Rubina, Matti Caspi and Popik Arnon,

Music: Matti Caspi

~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~

An Audio Recording of Leonard Performing during Yom Kippur War leonardcohenforum.com

"The link no longer works. If someone keeps this audio, I would appreciate it if you could send it to me. This is a remarkable document.

We had no audio and very few photos of Cohen during Yom Kippur War. The best known were taken by Yaakovi Doron and Isaac Shokal at Fa'id air base, then Ariel Sharon's headquarters, with Matti Caspi and Ilana Rubina. (I have 10.)

In those photos we see a technician of Army Radio recording, these tapes have been lost, according to Friedman. Maybe not, maybe we still have that "So Long, Marianne" included in that compilation".

ForYourSmile, Aug 14 2024.

Leonard Cohen at Sinai, October 1973

1973-00-00 The Army Radio Archive presents - What happened a long time ago.mp3 152MB 1:23:04

Isolate:

01 So Long, Marianne 4:49

02 Suzanne (interview and studio version) 4:44

From the text file attached with the audio of The Army Radio Archive:

“Now, an Israeli website claims to have

discovered an archival tape of artists performing for the

soldiers during the 1973 Yom Kippur war. The tape includes

Leonard performing “So Long, Marianne.” The following excerpt is

via Google Translate:

In honor of Yom Kippur this week, we bring you

the program of Yaakov Agmon “The Night in Egypt” in which he

brings the voices of IDF soldiers from the field during the Yom

Kippur War and the rare performances of Oshik Levi, Ilana

Rubina, Popik Arnon and none other than Leonard Cohen Private to

Israel in order to volunteer for the IDF and raise the morale of

the soldiers.

After the song and the applause, the narrator

says something like:

The applause was of course for Leonard Cohen.

And had you seen the way the soldiers welcomed him, you would

have witnessed genuine excitement. Before him [LC] Ilana Rovina

sang; they performed on a short break, while the soldiers rest.

And at around 46:39 (after an interview in

Hebrew) LC speaks and then starts singing again, probably

Suzanne. It seems that the recording then switches to the studio

version of Suzanne, not the live show, and returns to the live

show for the applause.

Leonard’s performance begins about 33:25".

Suzanne is the studio version, as it is said in the attached text document, by the way from a somewhat played vinyl record, but there is a valuable little previous interview.

From the rest of the audio, around minute 12, someone sings a fragment of “Romance a la Guardia Civil española”, if Cohen heard it, it must have caught his attention; it is a poem by Lorca that tells of the bloody attack against a gypsy village by the Civil Guard (military police in favor of landowners), even today that police is synonymous with torture and repression. Next is the ranchera “Allá en el Rancho Grande”. I find it curious that the animators of the Hebrew soldiers sang in Spanish.